by Joe Hughes

Many are familiar with the myriad of health benefits of using tea tree oil, but have you ever thought about how and why this Australian herb has ended up in small glass bottles on drug store shelves across the country? With benefits ranging from antifungal properties to aromatherapy, tea tree oil has become a staple of skincare, haircare, and naturopathic medicine in the 21st century. Despite its ubiquity in Walgreens and CVS, tea tree oil has a long, and sometimes murky, backstory of production and distribution that begins in its native ranges of Australia.

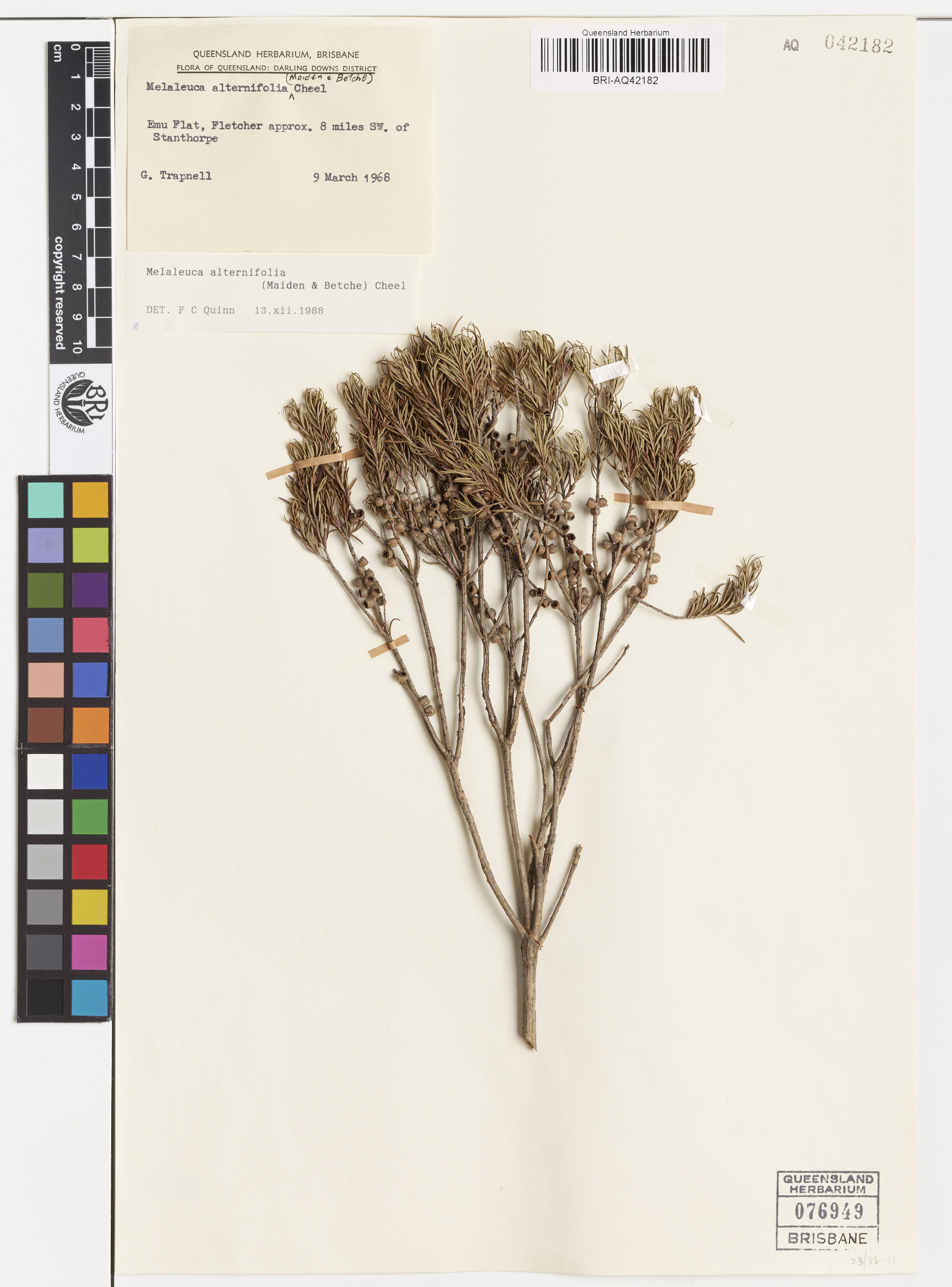

There are many species of plants across Australia and the Pacific that are referred to as “tea tree,” but this common name is generally restricted to species in the Leptospermum, Cordyline, Kunzea, or Melaleuca genera. While many of these species can yield oils when processed properly (i.e. Melaleuca dissitiflora, M. linariifolia, M. uncinata, etc.) the main source of commercially available tea tree oil today is Melaleuca alternifolia (Carson et al., 2006). This species is found natively near the border between the Australian states of Queensland and New South Wales, where it prefers to grow along streams and in swampy areas spanning from the coast to the inland ranges (PlantNET, n.d.)

Long before first Europeans arrived in Botany Bay in 1788, the Bundjalung people of northern New South Wales utilized M. alternifolia in a number of ways, ranging from inhalation of ground leaves to topical application of a poultice (Carson et al., 2006). The lasting effects of these treatments can still be seen in the continued popularity of tea tree oil, inspiring many scientific studies of M. alternifolia’s actual antimicrobial and antifungal properties.

Long before first Europeans arrived in Botany Bay in 1788, the Bundjalung people of northern New South Wales utilized M. alternifolia in a number of ways, ranging from inhalation of ground leaves to topical application of a poultice (Carson et al., 2006). The lasting effects of these treatments can still be seen in the continued popularity of tea tree oil, inspiring many scientific studies of M. alternifolia’s actual antimicrobial and antifungal properties.

The study of tea tree oil components by Hammer et al. (2003) demonstrated that a majority of the components found in the oil show the ability to kill Candida albicans, an opportunistic pathogenic yeast found commonly on the human body. In addition, an earlier study concerning the interaction between tea tree oil and Escherichia coli (E. coli) concluded that E. coli cells of various life stages died much faster in the presence of tea tree oil than under their regular autolysis, or self-destructing, processes (Gustafson et al., 1998).

Demand for the antimicrobial and antifungal properties of tea tree oil really began to increase to substantial numbers in the 1970s, as part of a “general renaissance of interest in natural products” (Carson et al., 2006). This required a transition from the crude, in-situ production that was the reigning method of acquiring oil from the M. alternifolia plants, to a commercial process capable of producing much more tea tree oil than could be produced before. Nowadays, M. alternifolia leaves and terminal branches are harvested, often from M. alternifolia plantations consisting of high-oil-yield cultivars, and put through a process called steam distillation. This process consists of steaming the plant material until the volatile tea tree oil is released and carried via steam to the condenser. There the steam and oil mixture is returned to its liquid state, and the liquid oil present is separated from the liquid water. This yields tea tree oil at a rate of 1-3% of the original mass of the plant material (Johns et al., 1992).

Demand for the antimicrobial and antifungal properties of tea tree oil really began to increase to substantial numbers in the 1970s, as part of a “general renaissance of interest in natural products” (Carson et al., 2006). This required a transition from the crude, in-situ production that was the reigning method of acquiring oil from the M. alternifolia plants, to a commercial process capable of producing much more tea tree oil than could be produced before. Nowadays, M. alternifolia leaves and terminal branches are harvested, often from M. alternifolia plantations consisting of high-oil-yield cultivars, and put through a process called steam distillation. This process consists of steaming the plant material until the volatile tea tree oil is released and carried via steam to the condenser. There the steam and oil mixture is returned to its liquid state, and the liquid oil present is separated from the liquid water. This yields tea tree oil at a rate of 1-3% of the original mass of the plant material (Johns et al., 1992).

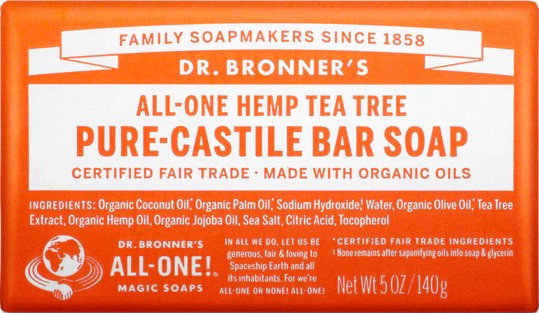

Since this increase in production and the commercialization of tea tree oil, countless uses for the essential oil have been found and shared amongst users and practitioners. The National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health reports that tea tree oil is promoted for use to combat “acne, athlete’s foot, lice, nail fungus, cuts, mite infection at the base of the eyelids, and insect bites” (NIH-NCCIH, 2020). The popularity of these uses is reflected in the wide range of tea tree oil-containing products available from many different producers. This popularity may also indicate the effectiveness of tea tree oil at combatting the microbes and fungi that are the main culprits in many of the aforementioned ailments. After all, if it wasn’t effective, would it have become as popular as it is today?

Since this increase in production and the commercialization of tea tree oil, countless uses for the essential oil have been found and shared amongst users and practitioners. The National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health reports that tea tree oil is promoted for use to combat “acne, athlete’s foot, lice, nail fungus, cuts, mite infection at the base of the eyelids, and insect bites” (NIH-NCCIH, 2020). The popularity of these uses is reflected in the wide range of tea tree oil-containing products available from many different producers. This popularity may also indicate the effectiveness of tea tree oil at combatting the microbes and fungi that are the main culprits in many of the aforementioned ailments. After all, if it wasn’t effective, would it have become as popular as it is today?

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a healthcare provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Photo Credits: 1) Bottles of tea tree essential oil (Stephanie (strph), via Wikimedia); 2) Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) in flower (PictureThis (https://www.picturethisai.com/wiki/Melaleuca_alternifolia.html)); 3) An herbarium specimen of Melaleuca alternifolia (courtesy of Queensland Herbarium, BRI); 4) A bar of Dr. Bronner’s tea tree soap (Drbronner.com)

References

Carson, C.F, K.A. Hammer, and T.V. Riley. 2006. Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil: a review of antimicrobial and other medicinal properties. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 19(1):50-62.

Gustafson, J.E., Y.C. Liew, S. Chew, J. Markham, H.C. Bell, S.G. Wyllie, and J.R. Warmington. 1998. Effects of tea tree oil on Escherichia coli. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 26(3):194-198.

Hammer, K.A., C.F. Carson, and T.V. Riley. 2003. Antifungal activity of the components of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 95(4):853-860.

Johns, M.R., J.E. Johns, and V. Rudolph. 1992. Steam distillation of tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 58(1):49-53.

National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Health information: tea tree oil (Internet). Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health. Accessed February 25, 2024. Available from: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/tea-tree-oil

PlantNET (Internet). 1991. PlantNET Profile for Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree). National Herbarium of NSW. Accessed February 25, 2024. Available from: https://plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/cgi-bin/NSWfl.pl?page=nswfl&lvl=sp&name=Melaleuca~alternifolia

Joe Hughes is a graduate of The George Washington University (2021) and in his 4th year as an ORISE intern at the U.S. National Arboretum Herbarium. In his free time he enjoys traveling, exploring public parks around Washington, D.C., and trying his best at pub trivia.