by David Zakalik

“Are you Jewish?”

I’ve lost count how many times I’ve been (good-naturedly) accosted with these words on a city sidewalk or college quad. The person speaking typically wears a black suit, white button-down, wide-brimmed black hat, and beard.

Chances are this man will have a ritual object in hand, depending on what Jewish holiday it is. In mid-autumn, he’ll be holding a bundle of foliage in one hand and a lemon-looking thing in the other.

These, respectively, are the lulav and the etrog. During the holiday of Sukkot, Jews the world over will take the lulav and etrog in their hands, say a blessing, and shake them in the four directions of the compass.

The etrog, better known as the citron (Citrus medica), is the fruit of one of four species used ritually during Sukkot. The lulav (the bundle of foliage) comprises a closed date palm frond (Phoenix dactylifera), and branches of myrtle (Myrtus communis) and willow (Salix alba).

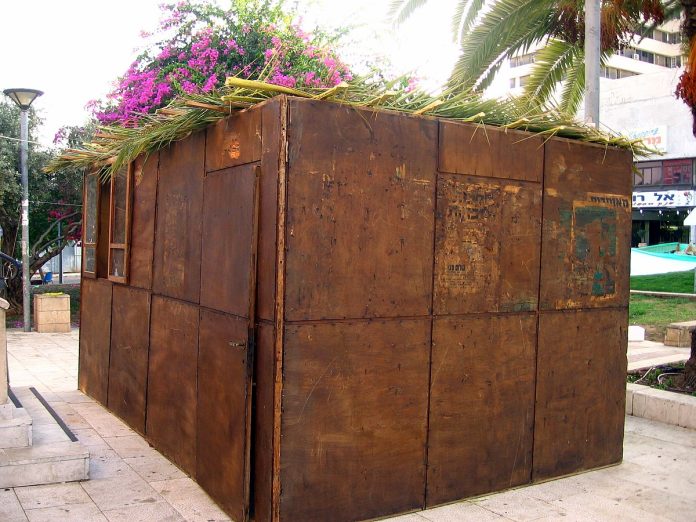

Part harvest festival, part commemoration of the Israelites’ forty years in the desert, Sukkot takes its name from the Hebrew word for “hut” (singular sukkah). Practicing Jews will construct a sukkah in their backyard or even on their apartment balcony and, for eight days and nights, eat meals in it. For those of us who don’t live in warm places, mulled wine and hot soup are a needed antidote to the autumn weather. The more observant (or hardcore outdoorsy types) will take all their meals in the sukkah, and even live in it for the duration of the holiday, but most of us are content with dinner. Inviting friends and family to your sukkah, and being invited to others’, is an important part of Jewish communal life.

Part harvest festival, part commemoration of the Israelites’ forty years in the desert, Sukkot takes its name from the Hebrew word for “hut” (singular sukkah). Practicing Jews will construct a sukkah in their backyard or even on their apartment balcony and, for eight days and nights, eat meals in it. For those of us who don’t live in warm places, mulled wine and hot soup are a needed antidote to the autumn weather. The more observant (or hardcore outdoorsy types) will take all their meals in the sukkah, and even live in it for the duration of the holiday, but most of us are content with dinner. Inviting friends and family to your sukkah, and being invited to others’, is an important part of Jewish communal life.

Rather like the fruit that got Adam and Eve into all that trouble, the Torah (Hebrew Bible) doesn’t mention the etrog explicitly by name. The biblical commandment is as follows:

…on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, when you gather in the produce of the land, you shall celebrate the festival of the Lord […] and you shall take for yourselves on the first day, the fruit of the goodly tree, date palm fronds, a branch of a braided tree, and willows of the brook. (Leviticus 23:39-40).

The knowledge that the fruit in question is Citrus medica comes down to us from ancient times via the Torah sh’bal peh (oral tradition) (Posner, n.d.). Unlike date palms, myrtle, and willow, the citron is not native to modern-day Israel. Originating in southeast Asia, perhaps in the westernmost foothills of the Himalayas, it probably came to the Levant via Media (now northwest Iran) (Langgutt, 2017). The species epithet medica is believed to refer to the ancient kingdom of Media, rather than to the fruit’s medicinal uses.

The knowledge that the fruit in question is Citrus medica comes down to us from ancient times via the Torah sh’bal peh (oral tradition) (Posner, n.d.). Unlike date palms, myrtle, and willow, the citron is not native to modern-day Israel. Originating in southeast Asia, perhaps in the westernmost foothills of the Himalayas, it probably came to the Levant via Media (now northwest Iran) (Langgutt, 2017). The species epithet medica is believed to refer to the ancient kingdom of Media, rather than to the fruit’s medicinal uses.

This interloper from the subcontinent is beautiful, fragrant, and unusual, but it isn’t the most practical herb: its albedo (rind) is thick, its flesh is small, and it isn’t the juiciest citrus fruit on the market. Why then did it become one of the symbols of the harvest—let alone of the Israelites’ return home from Egypt? I don’t know…but it’s a tradition!

Since at least the first century CE, Jews have grown or imported the etrog specifically for use in this one ritual. The etrog isn’t typically eaten on Sukkot, just held and shaken to fulfill the mitzvah (commandment) from Leviticus. Though the citron might have been traded through west Asia and the Levant in biblical times, the earliest evidence of it being grown in ancient Israel dates to the 5th or 4th century BCE, though not necessarily by Jews (Langgut, 2015). Archaeologists in Israel recently found citron pollen in the ruins of a Persian imperial estate outside Jerusalem, and the word etrog is thought to derive from Persian.

The first cultivation of citron in the Mediterranean predates the arrival of other citrus species by centuries.

Similar to the symbolic nature of its use in Judaism, it has been speculated that because of its pleasant smell and its rarity (especially in those days), the citron was initially traded throughout the Near East not as food or an edible herb, but as an elite status symbol.

Similar to the symbolic nature of its use in Judaism, it has been speculated that because of its pleasant smell and its rarity (especially in those days), the citron was initially traded throughout the Near East not as food or an edible herb, but as an elite status symbol.

However, C. medica does have some practical uses. Theophrastus, Democritus, and Pliny all note that, when placed among clothes, it repels moths. It has also been used to freshen breath. Oils from the flowers and rind were—according to the Andalusian botanist Abu Marwan—used as a stomach tonic (Arias, 2005).

In the Jewish tradition, an etrog can’t be considered suitable for use on Sukkot if it comes from a grafted tree. Though Jewish religious law (halakhah) allows for grafting of fruit trees onto rootstocks of the same species, the rabbis of the late 16th century engaged in a long discourse over the permissibility of using etrog fruit from a grafted tree. Can an etrog be considered the “fruit of the goodly tree” if it’s grown on a chimera of two different trees? Rabbis being extremely cautious about edge cases in religious law, they went for stricture rather than lenience. Not only can’t fruit from grafted trees be used, but fruit from a seedling grown from the fruit of a grafted tree can’t either (Nicolosi, 2005).

This controversy arose quite late—at least 15 centuries in! —probably because there hadn’t been other citrus species grown in the Mediterranean, where the rabbis in question lived, until the Arabic period. No other citrus species, no need to worry about interspecies grafting.

So important is this lumpy yellow lemonoid to Jewish religious practice, that many observant families even own a specially made etrog case, often made of silver, to honor and protect it. My family never had one that ornate—we made do with the Styrofoam-lined cardboard box the etrog arrived in each year. But the fact that many Jewish families own a special case for a fruit they don’t eat, that is only used for one week a year, speaks to the kavanah, the spiritual intentionality, with which Jewish people observe the holiday of Sukkot, and the spiritual significance of the etrog.

So important is this lumpy yellow lemonoid to Jewish religious practice, that many observant families even own a specially made etrog case, often made of silver, to honor and protect it. My family never had one that ornate—we made do with the Styrofoam-lined cardboard box the etrog arrived in each year. But the fact that many Jewish families own a special case for a fruit they don’t eat, that is only used for one week a year, speaks to the kavanah, the spiritual intentionality, with which Jewish people observe the holiday of Sukkot, and the spiritual significance of the etrog.

This past October, I visited a friend’s sukkah a few blocks away, and brought my nephew along. Though he got sleepy and had to go to bed before we could fulfill the commandment, I got a photo from his parents a few days later, showing the youngest member of the Zakalik family holding an etrog larger than his two hands put together.

The tradition lives on.

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Photo Credits: 1) Orthodox Jewish boys carrying lulav and etrog around the streets of Warsaw, Poland, likely so others can fulfill the commandment (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York); 2) Sukkah in Great Synagogue of Herzliya, Israel (Ron Almog); 3) Etrog fruit (Erin Holden); 4) Two men inspect etrogs for blemishes in Warsaw, Poland (N. Kuszer, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York); 5) Etrog flowers (Erin Holden)

References

Arias B.A., L. Ramón-Laca. 2005. Pharmacological properties of citrus and their ancient and medieval uses in the Mediterranean region. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 97(1):89-95.

Langgut, D. 2017. The history of Citrus medica (citron) in the Near East: Botanical remains and ancient art and texts. Agrumed. pp. 84-94, in: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean: acclimatization, diversifications, uses. Publications du Centre Jean Bérard, Naples.

Langgut, D. 2015. Prestigious fruit trees in ancient Israel: First palynological evidence for growing Juglans regia and Citrus medica. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences. 62(1-2):98-110.

Nicolosi ,E., S. La Malfa, M. El-Otmani, M. Negbi, E.E. Goldschmidt . 2005. The search for the authentic citron (Citrus medica L.): Historic and genetic analysis. HortScience. 40(7):1963-1968.

Posner, M. n.d. What is an etrog? Accessed October 20, 2024. Available from https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/746603/jewish/What-Is-an-Etrog.htm